Walk through the Exhibition

Walk through the Exhibition

Images and videos:

Maria Cardamone

Portraits:

Mustapha Ousellam

Texts:

Dr Lucas Haasis

With great support from Dr Oliver Finnegan (TNA) and Kim König (GHI London)

”My photographic approach aims at paying tribute to and representing the outstanding items found in the Prize Papers collection in such a way that their material features become apparent and are preserved on camera. One of the main goals of the materiality approach we developed as part of the project is to give the reader a sense of the history of the documents and artefacts themselves, and hopefully, a pleasurable visual surrogate for the physical touch, too.”

Maria Cardamone, Senior Photographer

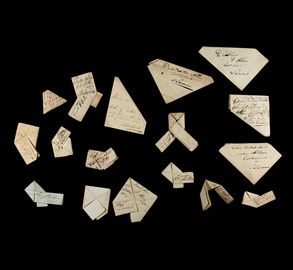

Letter Folding and Letterlocking Techniques

During an era when envelopes had not yet been invented, early modern letter writers used various folding and locking techniques in order to prepare their letters for postal despatch. They found innovative methods to fold paper and adhere different materials to their letters, in order to lock them and secure their contents from prying eyes.

In the Prize Papers, letters have survived in dozens of shapes and sizes. In the picture, we can see intriguing examples of letter formats including triangle, nonagon, pentagon or hexagon folds. They are from the private papers of Lieutenant George August Dossit D’Alban who sailed on the Sjælland, which was captured at the Cape of Good Hope in 1798. D’Alban was a member of a Freemasons’ lodge.

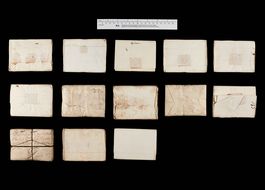

Sealed Letters

The Prize Papers contains more than 160.000 letters of which the majority have already been opened. However, several hundred letters have survived in their original folded and sealed condition, as if they have just been posted. In the picture, we can see some of the mail-in-transit, mostly Spanish letters, that were stored in mail bags on board the French ship Le Fort de Nantes, before it was captured in January 1747.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/111E

Panorama Shots

Thousands of letters in the Prize Papers collection have survived as letter packets. During the process of digitisation, this form of postal dispatch is preserved and documented. In order to image the arrangements of the letters, the Prize Papers’ photographers take panorama shots using a landscape lens that allows them to capture entire ‘trees’ of letters along with the enclosed artefacts.

Capturing the material arrangement of letter packets makes it possible to reconstruct correspondence networks, postal routes or the degree of intimacy between letter writers. It also points to the important but little known epistolary practice of early modern letter writers enclosing objects in their letters.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/99

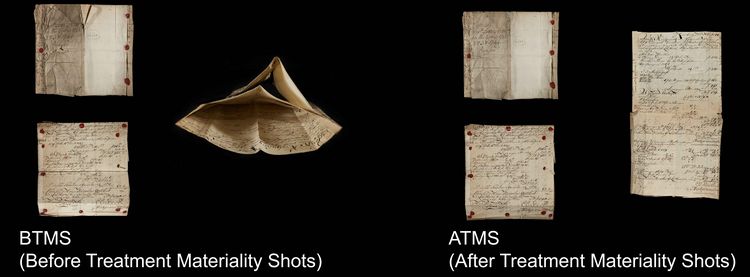

BTMS-ATMS Materiality Shots

In order to document alterations or repairs of the collection during conservation, the Prize Papers’ photographers take Before and After Treatment Materiality Shots, BTMS and ATMS. They do this before a document or object is digitised, allowing us to show the different conservation measures necessary to preserve the material or to make it accessible.

Follow the conservation process for a sales invoice that was found in the archive of the merchant Nicolaus Gottlieb Luetkens. This document was sealed several times by the court, because it represented valuable evidence against the ship’s owner, who claimed that the vessel qualified as neutral. The court officials reused the wrapper of the document.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 30/236

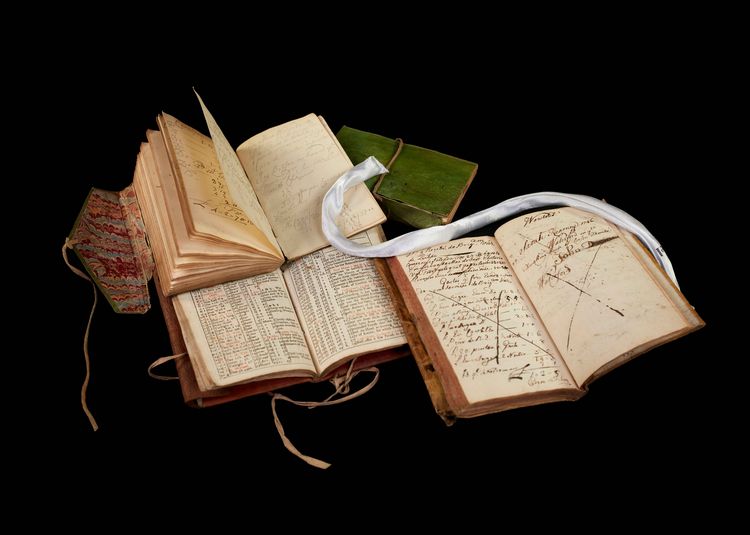

Notebooks of all Sizes

A practice that we sometimes encounter in the Prize Papers is that people did not just own one or several notebooks, but that they had volumes enclosed within one another. In the picture, we can see a yellow notebook found amongst the personal belongings of the captain of the Jungfrau Maria. Enclosed within the notebook are two other volumes written in very small print, Verbesserte Brem- und Verdischer Almanach from 1747 and Hamburgisch verbesserter Schreibcalender from 1746. In modern terms, we would call this book an early form of a Moleskine notebook.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/119/21

Books

Books were commonly used as evidence in the High Court of Admiralty. As a result, the Prize Papers holds many volumes that have survived in an astonishingly well-preserved material condition.

They are occasionally accompanied by other documents and objects, as is shown in the large court bundle captured in the image, consisting of a notebook with a pencil, a large official seal, bills of lading, and correspondence. All of this material was taken from the ship Azië in 1672.

In the image on the right, we can see several small notebooks that belonged to the Welshman John Davies, Captain of the Portuguese ship O Vas de Lisboa. They include two Gentlemen and Citizens' Almanacks, a pocket notebook and the almanac Vox Stellarum for 1743.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 30/642, HCA 32/119/21, HCA 32/157/22

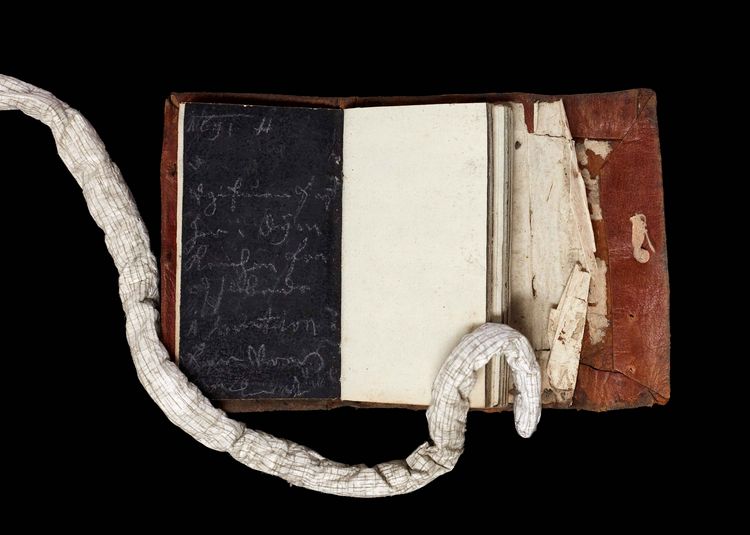

Chalk Writing

Some notebooks in the prize Papers collection contain chalkboard pages, often with writing in chalk or pencil. This highly fragile form of text could be wiped from the page with a single careless movement, so these books have to be handled with the greatest care. Digitising these pages ensures that such ephemeral writing is preserved for posterity.

Pictured is a notebook protected by a leather casing and a page of chalk writing in Kurrent, which is also known as cursive or German script. The book was created between 1689 and 1690, probably taken from the ship Catharina of Copenhagen.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/1827

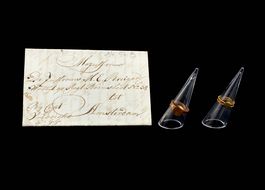

Gold Rings

These golden signet rings were found by our Dutch colleagues in 2017 while opening 75 still sealed letters from the English slave trade ship Diamond of London. During 1803, the vessel departed from Elmina in Ghana, a trade hub run by the Dutch that primarily sold enslaved people for onward transport to the Americas.

Due to the rings being sealed within the letter for centuries, they remain in a remarkable condition. The accompanying letter gives important details about the rings as its author, J.G. Coorengel, writes that he sends them to comfort his mother after the death of his father. He also states that these rings would show “what the blacks know how to make”, so they are an example of Ghanaian craftsmanship.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/996

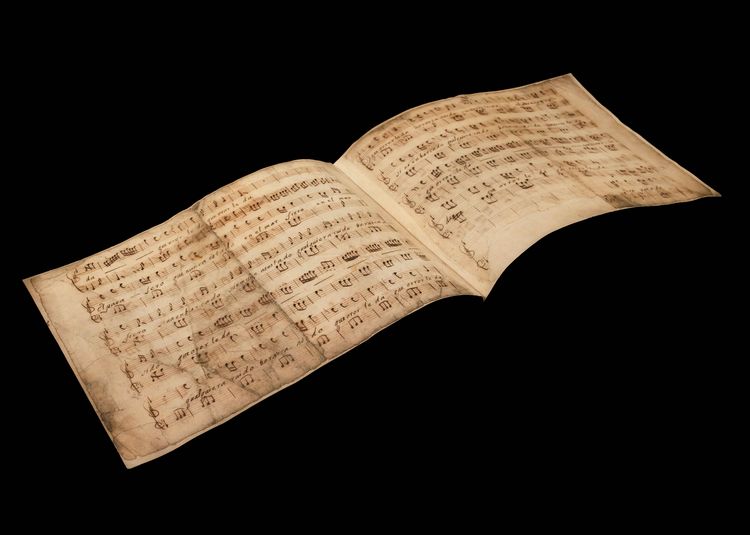

Sheet Music

Songs, sung together or instrumental music had an ancestral place in everyday life aboard ships and in ports during the age of sail. Music promoted cohesion and a sense of community among seafarers and helped them to cope with the hardships of life at sea. Therefore, it is not surprising to find sheet music in the Prize Papers.

Pictured is a music manuscript for both voice and violin labeled “Aria con violins” attributed to “Don Francisco Coradin” that was found among the crew’s papers of the ship Franciscus in 1744. It is a comic song in Spanish, describing the fears of passengers during their first voyage aboard a ship. We have not been able to find a record of this song elsewhere and it has probably never had a modern performance.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/111B

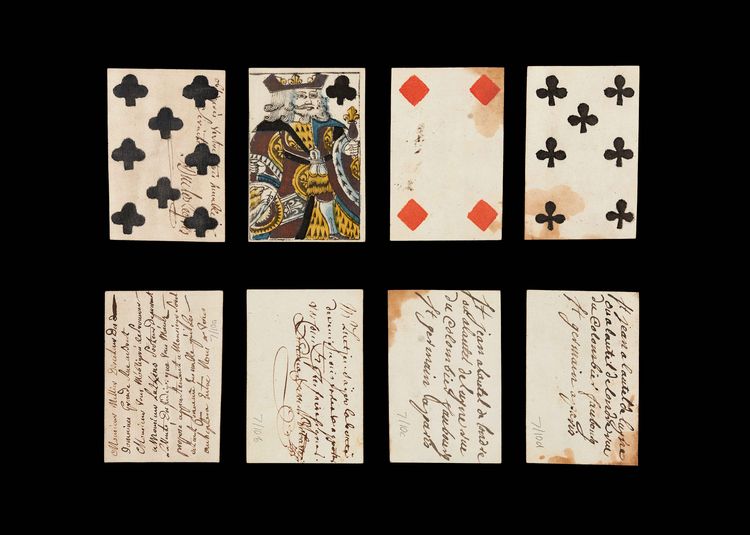

Playing Cards

Playing cards were a common item on board ships during the age of sail and, as a result, we often find them in the Prize Papers. As their appearance shows, however, these cards were not only used to play with or to gamble but the cards were also repurposed for a range of ‘secondary uses’, including as currency, business cards, IOUs, note paper and even official paperwork.

In the example we can see a set of four playing cards, found among the papers of merchant Nicolaus Gottlieb Luetkens. He used them as calling cards, with different names and merchant notations visible on each.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 30/232

Keys

The range of keys in the Prize Papers were either sent in letter packets or confiscated as part of the personal belongings of captured crewmembers or passengers.

The keys in the picture were seized following the Battle of Saldanha Bay, which took place in the waters around the Cape of Good Hope. There, on 21 July 1781, a squadron of Royal Navy warships under the command of George Johnstone captured five Dutch East India Company ships.

The exact use for each individual key is unfortunately lost. They most likely opened chests or doors aboard the five captured ships and became bundled up with the papers of each vessel, when the captors removed them.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 54/5

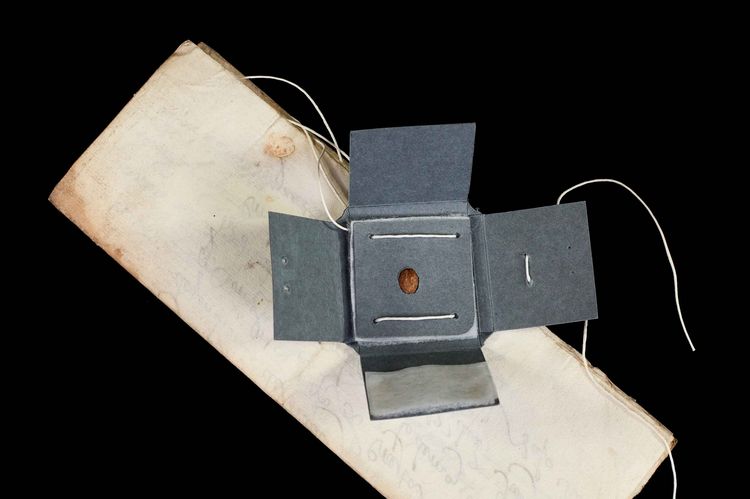

A Single Coffee Bean

The coffee beans in this image are something of a mystery. They come from the personal archive of Michel Le Pape, the second captain of the French ship Postillon of Nantes, which was returning from Martinique in 1747, when it was captured by a British privateer. Le Pape’s papers were then confiscated by the privateer crew and transported to England.

The letter that the beans were enclosed in is from Le Pape’s wife and discusses her pregnancy. Intriguingly, it makes no mention of coffee. We have several theories to explain the coffee beans’ presence: perhaps his wife used them to dry the ink before sending or they were a sample that Le Pape himself tucked away. Given that the letter discusses his wife’s pregnancy, it is also possible that the letter was a fertility charm, as coffee beans were sometimes associated with fertility in early modern Ethiopia.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/143/19

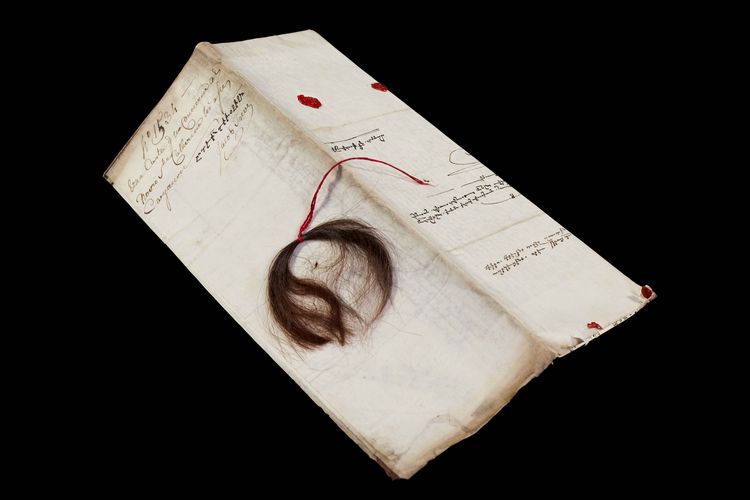

A Lock of Hair

During the early modern period, it was common practice for lovers or family members to send each other small tokens of affection enclosed in letters. Objects, such as miniature portraits, jewelry or even locks of hair, had a central place in maintaining and developing relationships over long distances.

This lock of hair was found during the digitisation of an Armenian letter from the ship Santa Catherina, which was leased to merchants from New Julfa, Isfahan. While it is a fascinating find for us today, the High Court of Admiralty evidently viewed the hair and its context differently – their translator wrote a “letter of no significance” on the back of the missive that the lock was enclosed in. We highly doubt that!

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/1832

The Prize System and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries, around 11,000,000 enslaved Africans were trafficked by Europeans to plantations in the Americas and elsewhere. British privateers and naval vessels had a significant role in this slave trade, as during wartime they intercepted enemy slaving ships. The prize system allowed these sailors to then claim ownership of the enslaved people that they captured. A British commander would argue before an admiralty court that the Africans he seized were legitimate “prize” and, if the court’s lawyers deemed the capture legal, then the enslaved people were condemned as “enemy property” and sold at a slave auction in the Caribbean. The prize system thus facilitated the enslavement and transportation of many thousands of Africans, although the exact scale of this activity is still unknown to us.

These captures mean that an unusually large number of documents and objects from the slave trade survive in the Prize Papers. The documents range from ship inventories, in which enslaved people appear only as numbers, to letters passed amongst slaving crews as they purchased captives across West Africa. Enslaved people are named in only a limited number of these records and very rarely have their own voice.

While this exhibition is focused on objects, it is important to acknowledge that many of them originate either from the slave trade itself or from the transportation of goods produced by enslaved laborers. This context is stressed throughout and, wherever possible, we have worked to bring the lives of enslaved Africans into the frame. The Prize Papers Project is committed to making our enormous holdings on the slave trade and life in plantation colonies available online and in open access.

Glass Beads

Glass beads such as these were not only used as jewelry. Today, when we admire the beauty, colorfulness and joyful designs of these artefacts, we should be aware that during the 17th and 18th centuries, countless strings of beads like these were shipped in barrels from Europe to Africa, to be used as currency and goods in the transatlantic slave trade.

The bead necklace pictured was found among letters coming from the fortress of Elmina, the headquarters of the Dutch slave trade in West Africa. They were addressed to relatives and famous merchant houses involved in the bead trade in Amsterdam, which was a centre of the jewelry’s production at the time. The beads shown here were intended as samples, to help merchants prepare more shipments.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/996/34