The Prize Papers and Transatlantic Slavery

The Prize Papers and Transatlantic Slavery

On Exploitation, Human Suffering and Injustice

Around 12.5 million enslaved Africans were shipped to the Americas by Europeans between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries and were forced to work in colonies.

The Transatlantic Slave Trade and the plantation system that it enabled remains one of the biggest crimes against humanity and one of the largest injustices in human history, and its consequences remain with us today, through inequality between the global north and south, anti-black racism and political instability across the African continent.

Almost all of the documents and objects in this exhibition come from recently discovered materials in the UK National Archives’ Prize Papers, an archival collection of around 500,000 letters, papers and objects taken from 35,000 ships captured between 1652 and 1815 by the British. To weaken an enemy’s economy during wartime, European states commissioned privateers and naval vessels to capture enemy shipping, so-called “prize taking”. Admiralty courts then ruled on a capture’s legality, using papers taken from the ships as evidence. As many of the vessels seized by the British were involved in the slave trade, the letters and other records on these ships display callous disregard for human life in pursuit of profit.

Engaging with these original sources offers a more personal view of transatlantic slavery, bringing both individual enslaved people and their enslavers into focus. The materials featured here show the workings of this enduring institution in harrowing detail and reveal the myriad of ways that Atlantic slavery changed the course of history, in Africa, Europe and the Americas.

Glass Beads, c.1803

This glass bead necklace was manufactured in Amsterdam around 1803 and intended for the slave trade in West Africa, where European traders exchanged strings of beads for enslaved people. These beads were enclosed in a letter sent from Elmina Castle (in Ghana, today), to Amsterdam as a sample of what to include in future shipments.

Goods that Europeans sold in West Africa were often manufactured, luxury items to be consumed by elites. They had influence on culture across West Africa, with beads in this style still worn in Ghana today.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/996

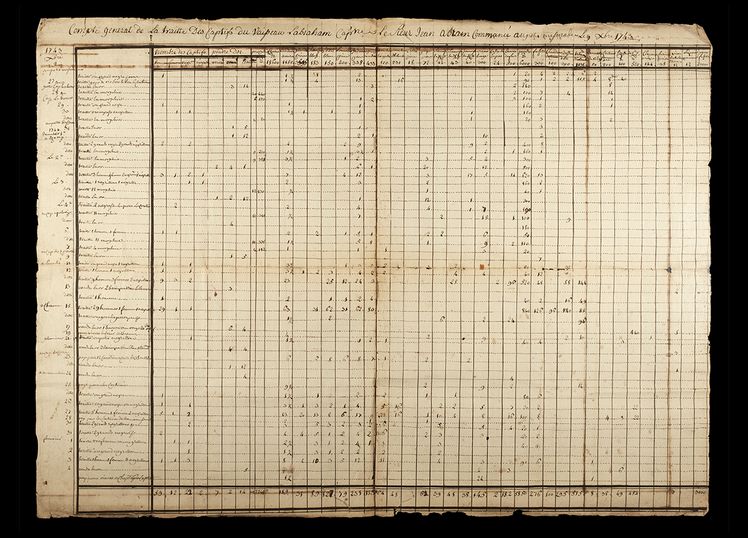

Slave Trade Grid, 1743

Reminiscent of a spreadsheet, this paper from the French ship Abraham of Nantes was used to track the 304 enslaved people its crew purchased from Monrovia in Liberia to Ekpe in Benin. The leftmost column lists the number of men, women, children bought each day, while numbers in the rows indicate goods exchanged for them, including, cowrie shells, cloth, and wine.

Slave trade ships kept meticulous accounts, far in excess of what other merchant vessels carried. Accounting reduced the enslaved to numbers, usually rendered them nameless and sanitised the slave trade’s barbaric practices.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/97/1, B5

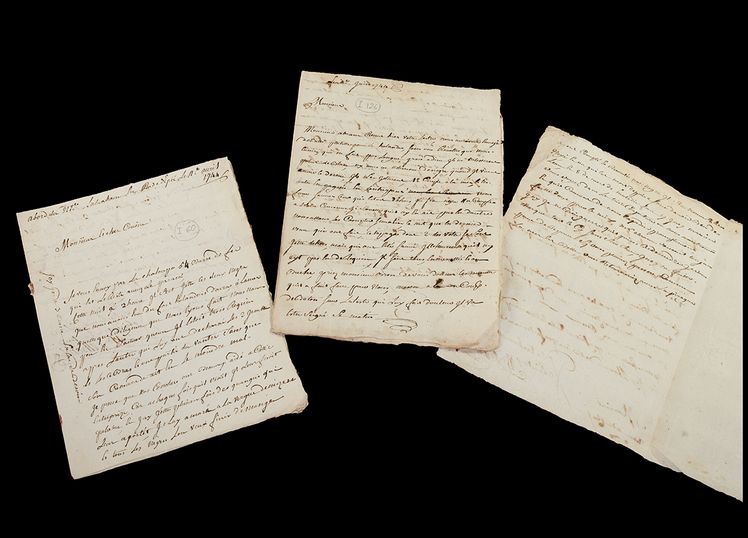

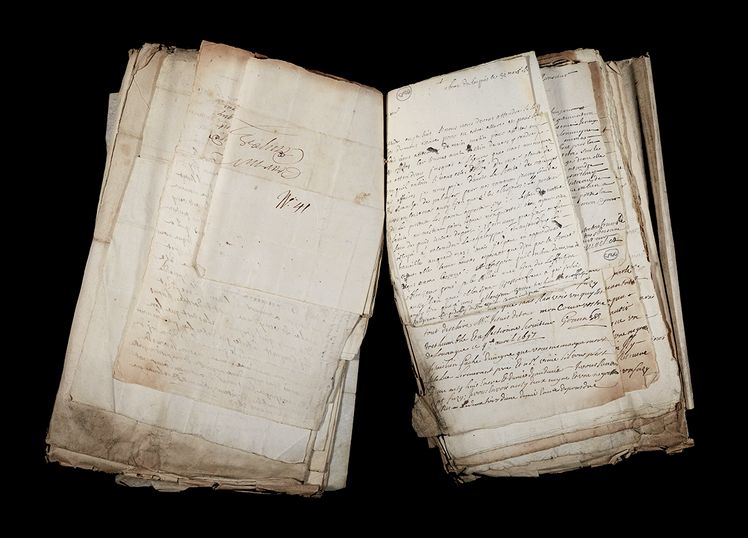

A Slave Revolt, 1 June 1744

This set of letters recounts an uprising of enslaved people aboard a French slaving ship, almost a month before the ship’s departure for America. Such rebellions were common and often bloody, but there is little evidence of them in official accounts.

In this case the revolt was unsuccessful. One of the letters from a crewmember states ‘thank God they did not injure any whites, nor did we injure any ***. When they realised they were going to be defeated, twelve pairs threw themselves into the sea ... it's a good thing there were no sharks.’

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/97/1, no. i60, i126, i129

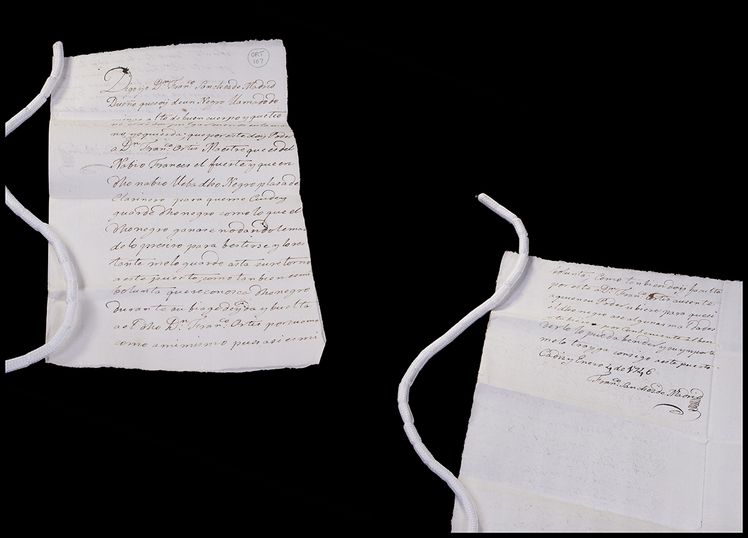

Loan Agreement concerning “Domingo”, 4 January 1746

In this legal document, the Spanish merchant Francisco Sanchez de Madrid lends an enslaved man, “Domingo”, to the ship captain Francisco Ortiz. It describes “Domingo’s” appearance, stating that he was tall, well-built, and missing a finger on his left hand. “Domingo” was to be a crewmember on Ortiz’s ship, perhaps a cook, but the agreement states that if he misbehaved then the captain could sell him.

Many enslaved men were forced to work on ships during the early modern period and some even had to work on slave trade vessels.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/111D/5, ORT 107

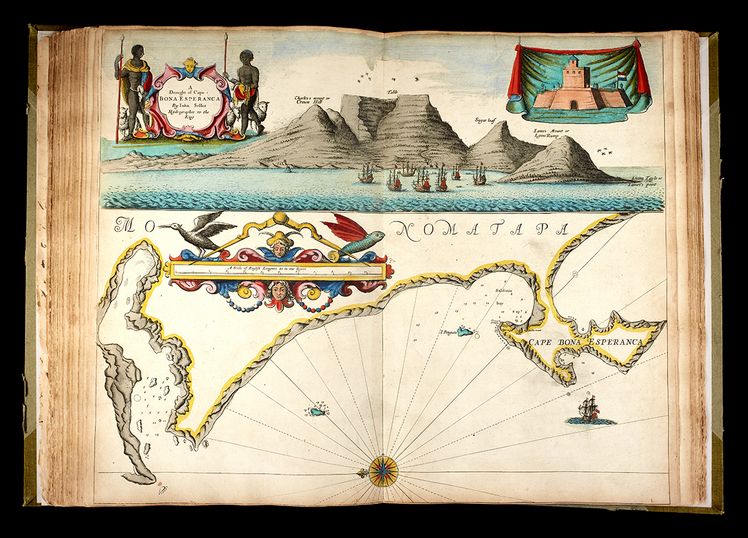

Map from the Atlas Maritimus, 1698

A colourful, illustrated map of the Cape of Good Hope (in South Africa, today) with a view of Table Mountain. In the top left, two men are depicted as shepherds, perhaps intended to be from the Khoekhoen or San peoples.

The building in the top right is an impression of the Dutch slave trade fort at the Cape. Similar strongholds were established by European companies across coastal Africa, where enslaved people were held in cramped rooms, pens and dungeons, until a ship arrived to transport them across the Atlantic.

The National Archives, ref. FO 925/4111

Letters to French sailors, 1697

This set of fifty letters came from the French ship Concord of La Rochelle, which traded for enslaved people across the Kingdom of Loango (in Southern Gabon, today). Written between crewmembers, the letters detail their negotiations with local merchants and rulers to buy enslaved people.

Africans purchased by slavers had often been captured in the continent’s interior during wars and sold several times before they reached the coast. As the transatlantic slave trade created enormous demand for human cargo, it likely incentivised African elites to wage war and seize captives.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/1865/24

Gold Rings, c.1803

Two gold rings discovered during the opening of 75 still-sealed letters from the English ship Diamond of London, which was engaged in the slave trade at Elmina Castle (in Ghana, today). Elmina was a trade hub run by the Dutch that primarily sold enslaved people for onward transport to European colonies in the Americas.

The rings were crafted by Ghanaian artisans, who may have been enslaved themselves, and were enclosed in the letter pictured, intended for the sender's mother to comfort her following the death of her husband.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/996

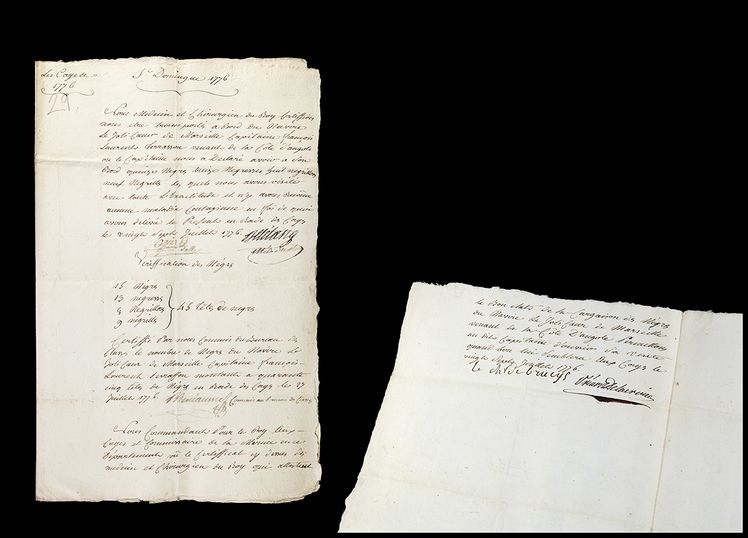

Medical Certificate, 27 July 1776

Issued by a French surgeon at Les Cayes in Saint Domingue (Haiti, today), this certificate states that the enslaved people aboard the ship Joli Cœur were free from infectious disease. It had a commercial purpose, as buyers would not want to purchase an enslaved person who was ill.

These Africans had been shipped around 10,000 km from Angola and with so many people packed tightly into a ship’s hold, diseases such as typhus could spread rapidly. Without care or ceremony, the ship’s crew would throw captives who died on voyages overboard.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/370/21, no. 29

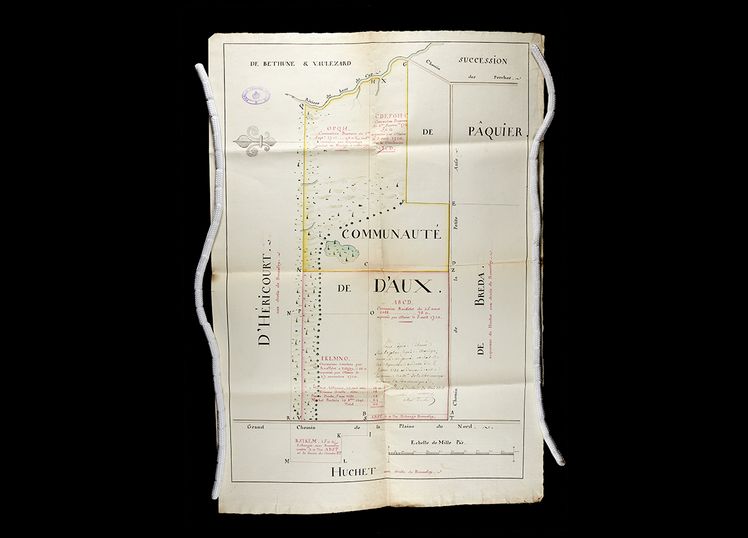

Plan of the Commune of D’Aux, c.1779

A coloured plan of lands on Saint Domingue (Haiti, today). Located south of Cap‑Français on the island’s northwest, the lands are divided between several owners, including the Hericourt (left) and Breda (right) families. In the centre are the estates within the Commune of D’Aux.

Notably, the sugar plantations that blanketed the island, and the thousands of enslaved people who worked them, are not pictured. This plan was drawn up in Saint Domingue and sent to France on the ship Quartier Morin, probably as part of a boundary dispute between plantation owners.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/435/1, No.133

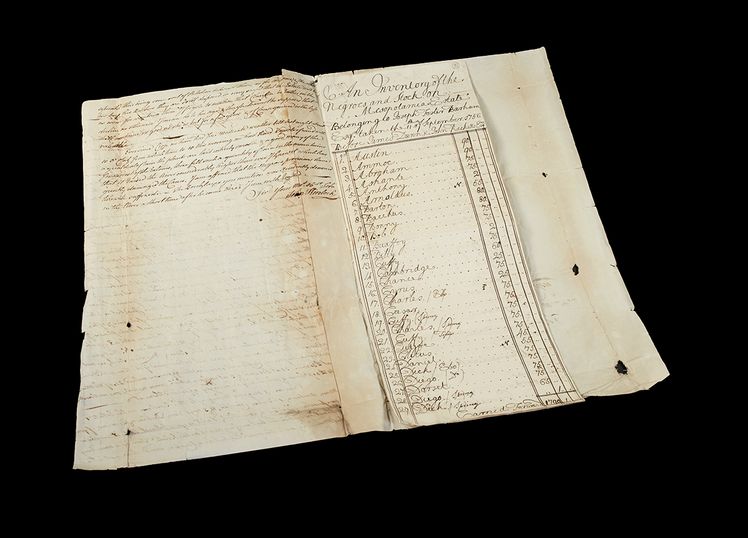

Inventory of the Mesopotamia Estate, 11 September 1756

A list of all goods and chattels belonging to the Englishman Joseph Foster Barcham, on his estate in Jamaica. The enslaved people that Foster owned are listed as property, giving their names and total value in pounds.

These were not birth names, but those allocated by enslavers as the institution of slavery worked to erase much of the individual’s prior identity. On this list, “Anthony” and “Buaffoy” are only valued at £2, probably because they were either too elderly or disabled to work.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 30/259, no. 91

Printed Cottons, c.1780

These examples of printed cotton are from Suriname and perhaps originate from the plantations of Zeldenrust, Welgelegen, and Voorburg. They were previously enclosed in letters written by Dutch merchants, who sent the cotton samples to Amsterdam on the American ship Illustrious President.

Colourful, printed cottons made with South American dyes were a sought-after commodity, in Europe but also in Africa, where they were exchanged for captives. In Suriname, enslaved women who worked in households wore elaborate clothing on special occasions made from such fabrics.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 65/8

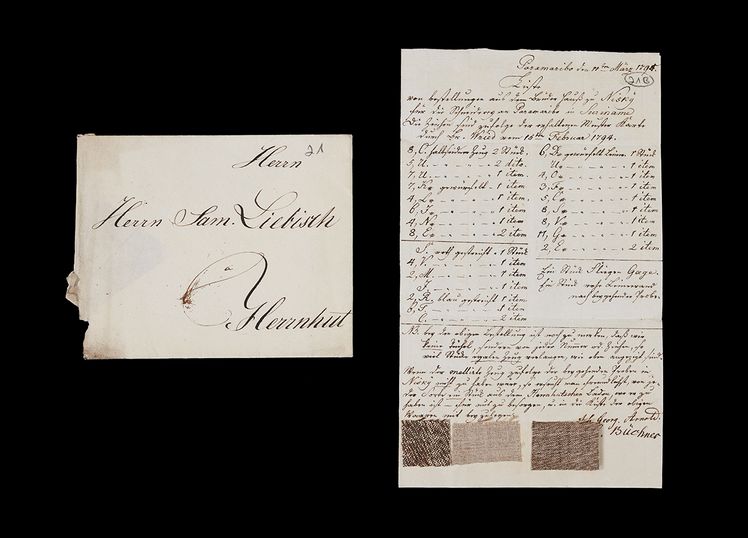

Letter with Fabric Samples, 11 March 1794

Religious groups also had a role in plantation slavery. The German Moravian Church justified enslavement on religious grounds, claiming that Christianity required hard work – convenient beliefs for plantation owners.

This letter to Saxony is accompanied by fabric samples from Moravian tailors. As one of the many trades that supported transatlantic slavery, textiles from Thuringia, Saxony or Silesia were shipped to the colonies for many purposes, including clothing for the enslaved. In Moravian tailor shops, enslaved people could be trained as tailors, receiving fabrics as wages.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 30/374

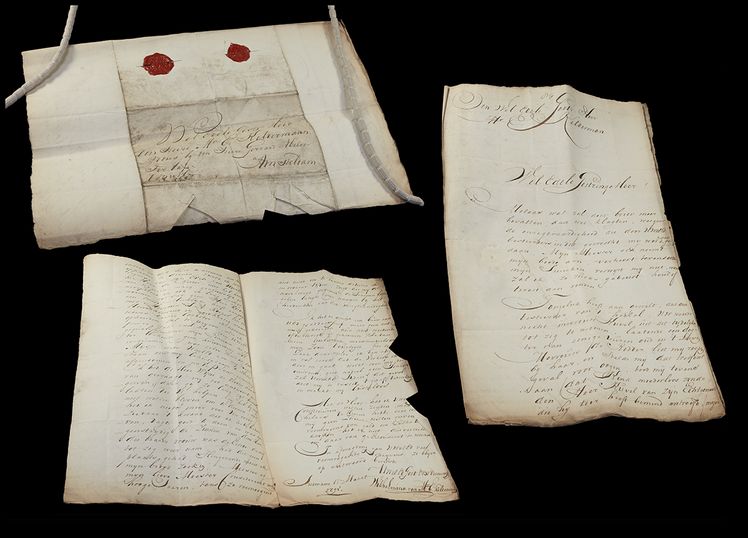

Letter by Wilhelmina, 14 March 1795

Wilhelmina van Kelderman, who had previously been enslaved on the Dutch plantation of Portorico in Suriname, sent this heartbreaking letter to her former enslaver, Engelbertus Kelderman, in Amsterdam. It states that although she had managed to buy her freedom, her son, Dauphin remained in bondage. She implores Kelderman to help him gain freedom.

The letter never arrived, and we are uncertain whether her request was fulfilled. Nonetheless, her writings are highly significant, as records written by those who endured slavery are seldom preserved in archives.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/690-1

A Basket, c.1747

This basket was taken from the French ship Le Printemps, which was captured en route from Saint Domingue (Haiti, today) to Bordeaux. The ship’s captain used the basket to store his personal letter archive.

It is hand-woven and features knotted handles made of hair and a mud-painted frieze. In terms of its origins, the basket was likely crafted by an enslaved African woman in Saint Domingue and the craft traditions evident in the basket, notably the mud painting, could trace the maker’s origins to Senegal, Gambia or Mali.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/142/26/1

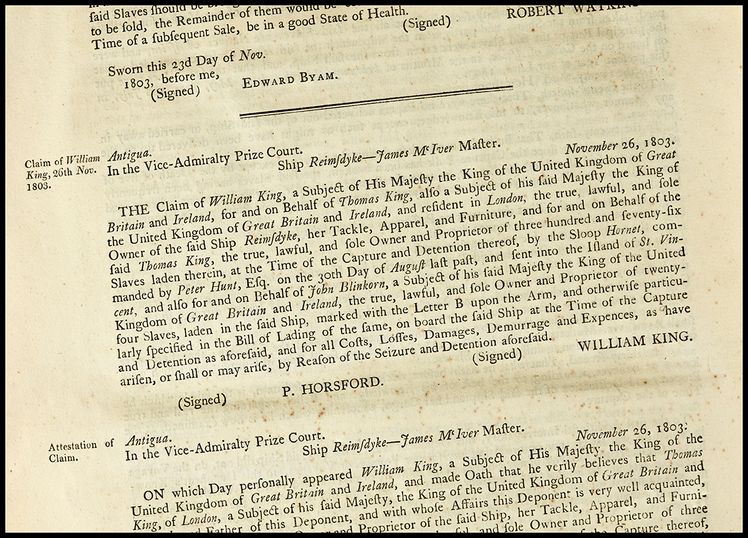

Printed Prize Appeal, 1807

Pictured is an extract from a legal appeal, issued by the Vice-Admiralty Court of Antigua. Colonial vice admiralty courts heard prize cases and if the legality of a capture was heavily contested, it could be appealed to the High Court of Admiralty in London.

This appeal contests the capture of the British slaving ship Reimsdyke that was carrying 405 enslaved people, who were claimed by the crew of HMS Hornet, the captor. Privateers and navies used the prize system to trade enslaved people on a scale we are yet to understand.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 45/51/28

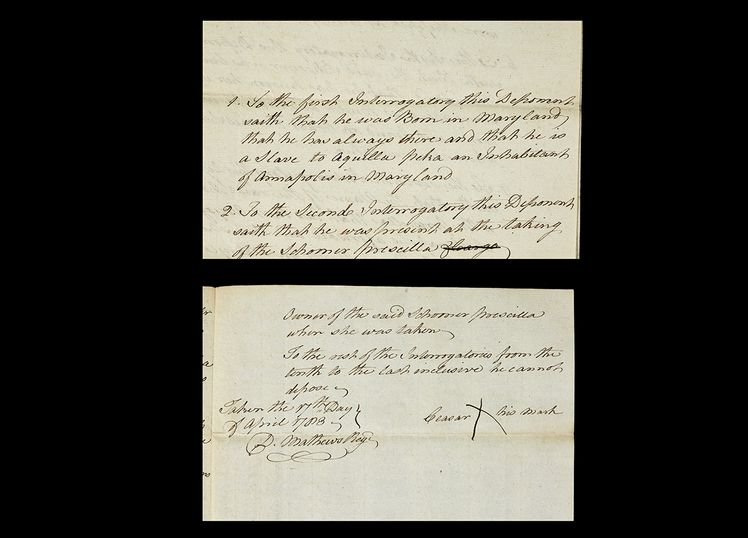

Deposition of “Caesar”, 17 April 1783

Extracts from a legal statement by “Caesar”, an enslaved man born in the colony of Maryland. He was on the American ship Priscilla that was captured by the British during the American War of Independence and carried into New York City. The Vice Admiralty Court there recorded this statement and, unable to write, Caesar signed with his mark.

While his voice is mediated by a court clerk, this deposition is a significant archival imprint for an enslaved person. Most survive only as numbers in merchant and plantation accounts.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/430/3, no. 2

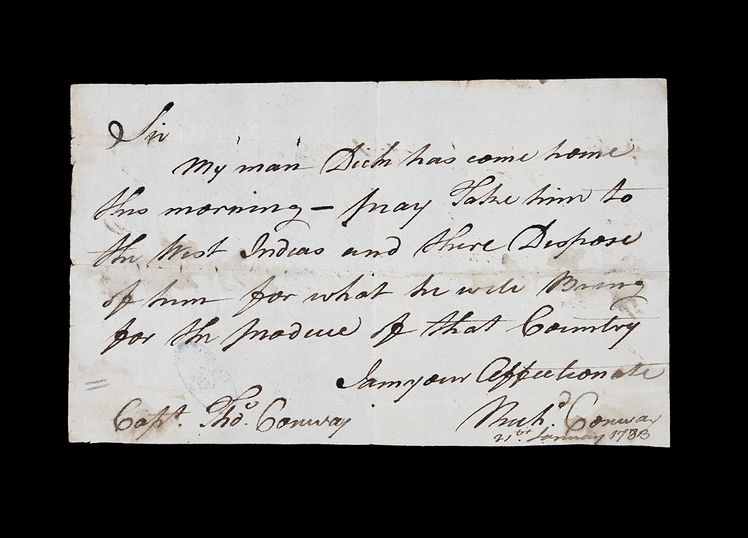

Letter to Thomas Conway, 21 January 1783

A brief note sent by the American merchant, Sampson Appleton to the ship’s captain, Thomas Conway. He instructs Conway to take “Dick”, who was enslaved by Appleton, to the Caribbean and sell him for plantation goods. “Dick” had likely run away but then returned, due to hunger, family commitments or fear of reprisal.

This short letter reminds us that enslaved people could be sold multiple times, between far distant owners and places. Each time they had to leave behind everyone they knew, including families and friends.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/446/11

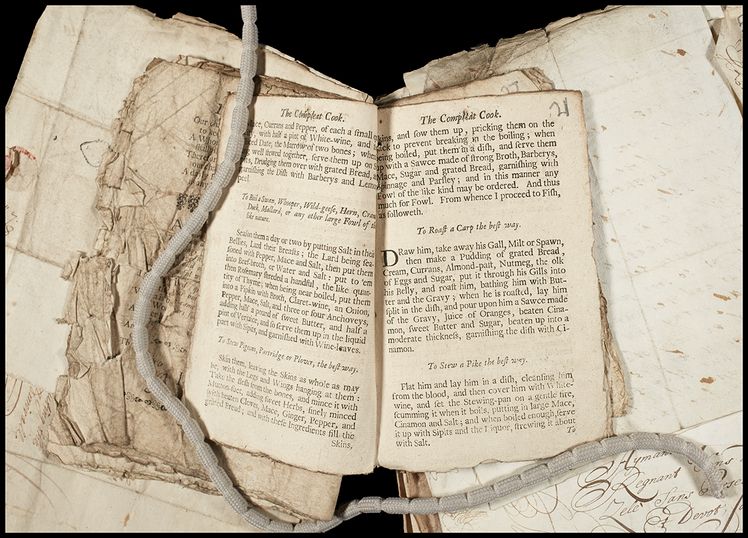

The Compleat Cook: or, the Whole Art of Cookery, 1694

Pages of a recipe book are visible in this mass of papers, which belonged to the Englishwoman Isobel Reay. It includes many recipes that incorporate sugar, including how ‘to roast carp the best way’ (right).

Sugar was made cheap in Europe by the toil of enslaved people across the Americas. Cutting sugar cane was hard labour, requiring razor-sharp tools, and the harvested cane was then milled and boiled in enormous vats. This highly skilled but forced labour often left enslaved people missing limbs and with permanent disabilities.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/1879, no.16

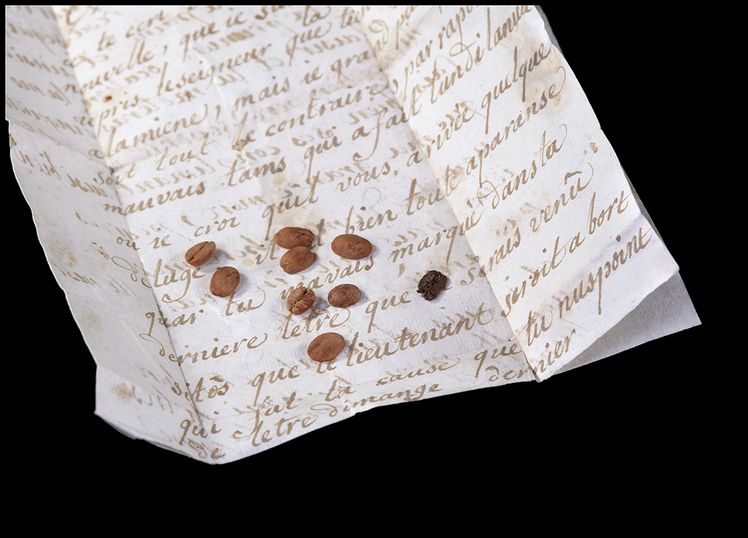

Coffee beans, c.1746

These arabica coffee beans were found enclosed in the letter pictured, which was sent to the French captain Michel Le Pape by his mother. They are most likely an early example of coffee from Martinique. Like sugar and tobacco, coffee was cultivated by enslaved Africans across the Caribbean and Central America. Each of these plantation goods were addictive, promoting continuous consumption in Europe.

Coffee plantations relied on enslaved labour as picking the crop was exhausting work conducted in sweltering climates. Pulping and roasting the crop was arduous but specialised work.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/143/19, A4

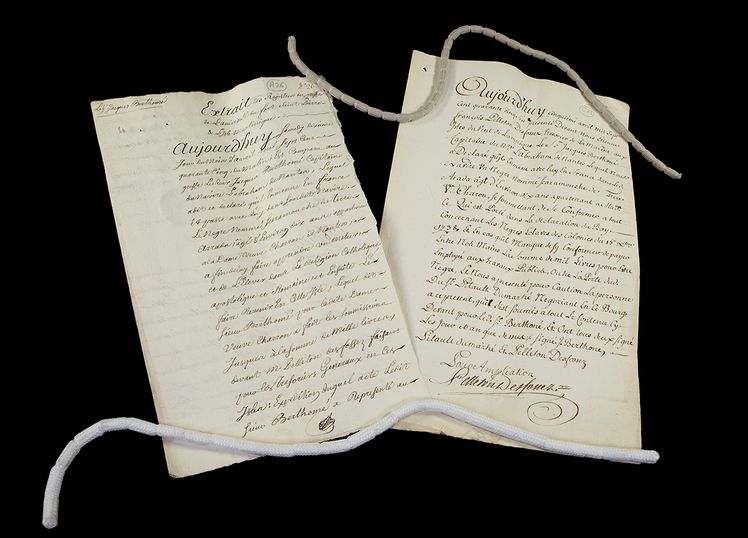

Permits for “Scaramouche”, 1743

While chattel slavery was technically illegal in Europe, there were circumstances that allowed enslavers to circumvent the law.

These permits, granted by the French Governor of Martinique, allowed for a 10-year-old boy referred to as “Scaramouche” to be shipped to France. He came from the Kingdom of Arada in Benin and the permits indicate that he was destined for the widow Charron in Nantes, who aimed to “teach him a trade and educate him in the Catholic religion before sending him back to this island.” His fate remains unknown.

The National Archives, ref. HCA 32/97/1, A 26, C 23

Maria Cardamone

Dr Lucas Haasis

Dr Oliver Finnegan

Advisor: Misha Ewen

With great support from Lisa Magnin, Annika Raapke, Camilla Camus-Doughan and Hilde Neus

Content Warning:

Some of the documents included in this exhibition are distressing, but we feel it is important to include them in order sufficiently represent the topic of the exhibition. We have removed offensive language and use quotation marks for the names of enslaved people to acknowledge that these were names given to them by their enslavers.